Benedict Evans sees virtual reality going back into hibernation:

We tried VR in the 1980s, and it didn’t work. The idea may have been great, but the technology of the day was nowhere close to delivering it, and almost everyone forgot about it. Then, in 2012, we realised that this might work now. Moore’s law and the smartphone component supply chain meant that the hardware to deliver the vision was mostly there on the shelf. Since then we’ve gone from the proof of concept to maybe three quarters of the way towards a really great mass-market consumer device.

However, we haven’t worked out what you would do with a great VR device beyond games (or some very niche industrial application), and it’s not clear that we will. We’ve had five years of experimental projects and all sorts of content has been tried, and nothing other than games has really worked.

Benedict Evans, The VR Winter

Like the supporter of a perennially mid-ranked football team, I too get my hopes up about VR every dozen years or so.

In the long-term, as with AI that passes the Turing Test, ubiquitous VR seems inevitable.

Why wouldn’t we spend our time in VR if some of these were true:

- It was prettier than reality

- It was easy to get things done there

- It was possible to get the impossible done there (fly, visit Mars, have sex with your favourite Hollywood crush)

- It was safer

- It emitted less CO2

Like AI, VR also runs aground on the shores of reality.

The journey from “Wow!” to “Wait! What?” for 2020’s incarnation of Amazon Alexa is about two minutes of interaction.

It’s even shorter with VR.

It seems clear that throwing Moore’s Law at the problem will eventually bodge together a solution.

The snag is you can’t be confident the Moon won’t have crashed into the Earth before then.

Don’t believe the hype

I think VR has a branding problem.

Reality is today not easy impossible to recreate, whether it’s a sassy live-in helper named Alexa or a virtual reality New York.

Don the headset to try any good VR game, and you’re bedazzled by the transportation.

If the game is great – Half-Life: Alyx is the state-of-the-art – then there’s at least one or two mechanics that suggest we’re finally on the cusp of our William Gibson future.

But then you poke a non-player character in the face and he says nothing.

Or you can open a drawer but not a door.

Or you bump into your sofa.

Wait! What?

A moment ago you were there – somewhere.

Now you’re a child with a wind-up toy monkey clanging cymbals, frustrated it’s already run out of tricks.

Game over

I think Virtual Reality has a branding problem.

If the label on your tin promises ‘reality’, it’s always going to smell off when you open it.

True, half my wish list for VR involves recreating reality.

But more than half of it doesn’t.

Imagine if the first video game developers had tried to recreate a photo-realistic Wimbledon before they’d got started with Pong.

Or if Space Invaders really had to look like the world was being invaded by aliens before it shipped.

Instead, their creators used what they had to make super-stylised reductions of reality – and in time games did take over the world.

You might argue today’s VR games are the baby step equivalents of Pong or Space Invaders.

I disagree.

Today’s VR developers try to use the graphical fidelity you’d get in the best of today’s games to conjure up their virtual realities.

Doing so, they set up their own failure:

The game can’t generate its world on demand. This means every playable option has to be worked out in advance by a game designer. Which means there can’t be many options. Which isn’t like our reality.

The game can’t visualise its world on demand. This means every environment has to be created by game artists, or at best compiled from a limited set of props. Because game artists, money, and storage capacity are all finite, this means the world can’t be very large. Slash it has to be tiny. Which isn’t like our reality.

The game world doesn’t behave like our world. This means that while it might look like our world for an instant, an instant later it doesn’t. So it’s not virtual reality. It’s not even camping in the pit of the uncanny valley. To be honest it’s not even looking at the uncanny valley on a map.

A solution: Virtual unreality

What if VR designers stopped trying to wow us with the theatrics of recreating a real-world office, a lifelike shark cage, or of running away from a flesh-and-blood zombie, and instead focused on creating their own realities?

Simple shapes. Limited colours. Narrower rules. Not many things you can do.

What if it was less 2018’s Annihilation and more 1979’s Asteroids?

I’m not suggesting someone create a VR shoot-em-up like Asteroids. They already have.

I’m suggesting tackling the problem at a higher level.

Maybe your virtual unreality (VU) world has rooms. Maybe it has doors and floors. Maybe it has some physics.

Maybe it contains ten objects. Maybe just three.

And that’s all it has.

But these three to ten things all interact in your VU in a completely internally consistent way.

Your VU engine can cover any eventually, which is important because it means it can generate VU on-demand, on-the-fly.

Say I’m walking towards my real-life sofa – the VU can put something in my way, or curve an in-VU pathway to take me away from it.

If that hack takes me into a new space that previously wasn’t on the VU engine’s map, it doesn’t matter because the alternate world is simple enough that the engine can adjust accordingly, and the dance I did doesn’t violate any internal rules.

You’re in a place. Nothing is wrong, because you can’t do much – but everything you can do you can do.

Why not start with these simple building blocks? Work outwards from there?

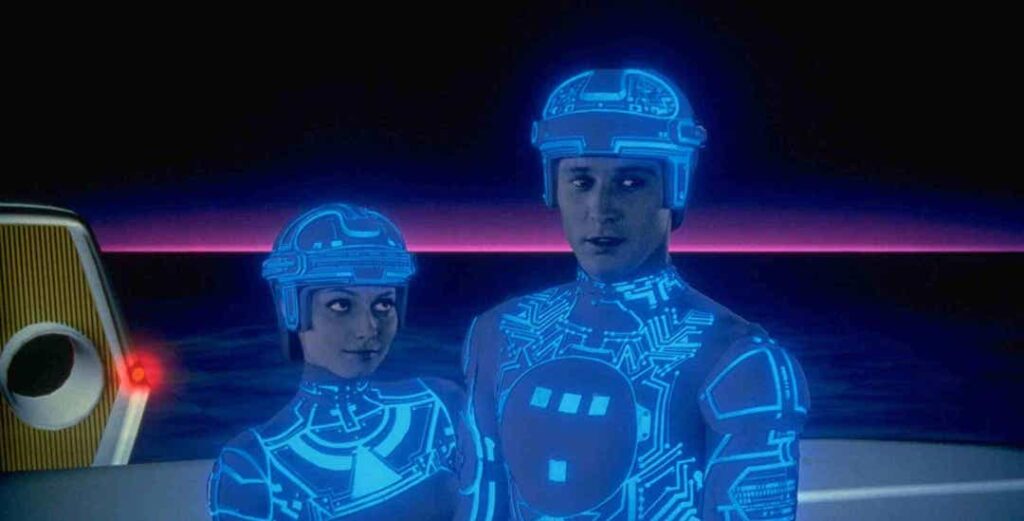

Less Matrix. Less Tron, even.

More Flatland.